|

My Casebook 2015-09-09 Extreme Endodontics, or Plain Common Sense? A Case Report The patient, a senior female government official of an European country, was posted to Mozambique for an extended period. Prior to her departure for Africa she consulted her dentist in Europe for her complaint of vague discomfort in the right maxilla.

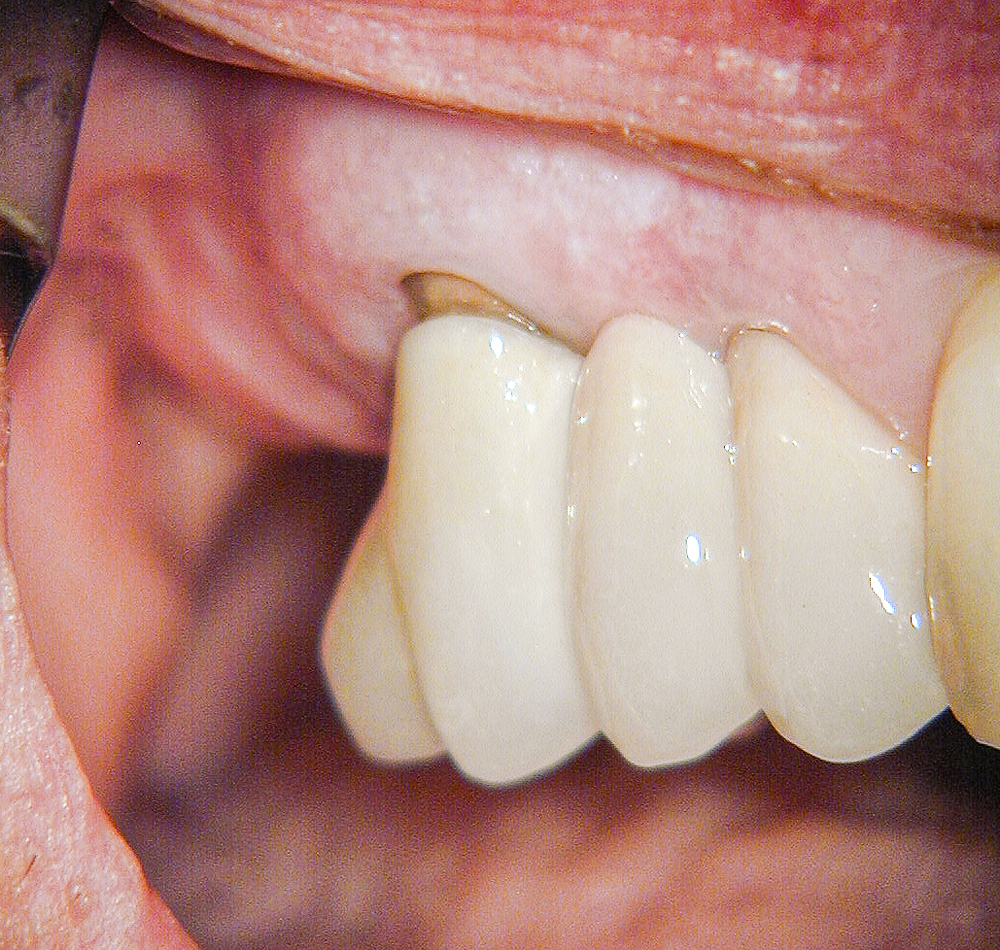

Examination showed the presence of a fixed three unit porcelain veneered to metal bridge in the right maxilla consisting of abutments on the first (presumably) molar and first premolar supporting a pontic replacing the second premolar. The distobuccal root of the molar abutment tooth was completely exposed by periodontal recession. (Figure 1)

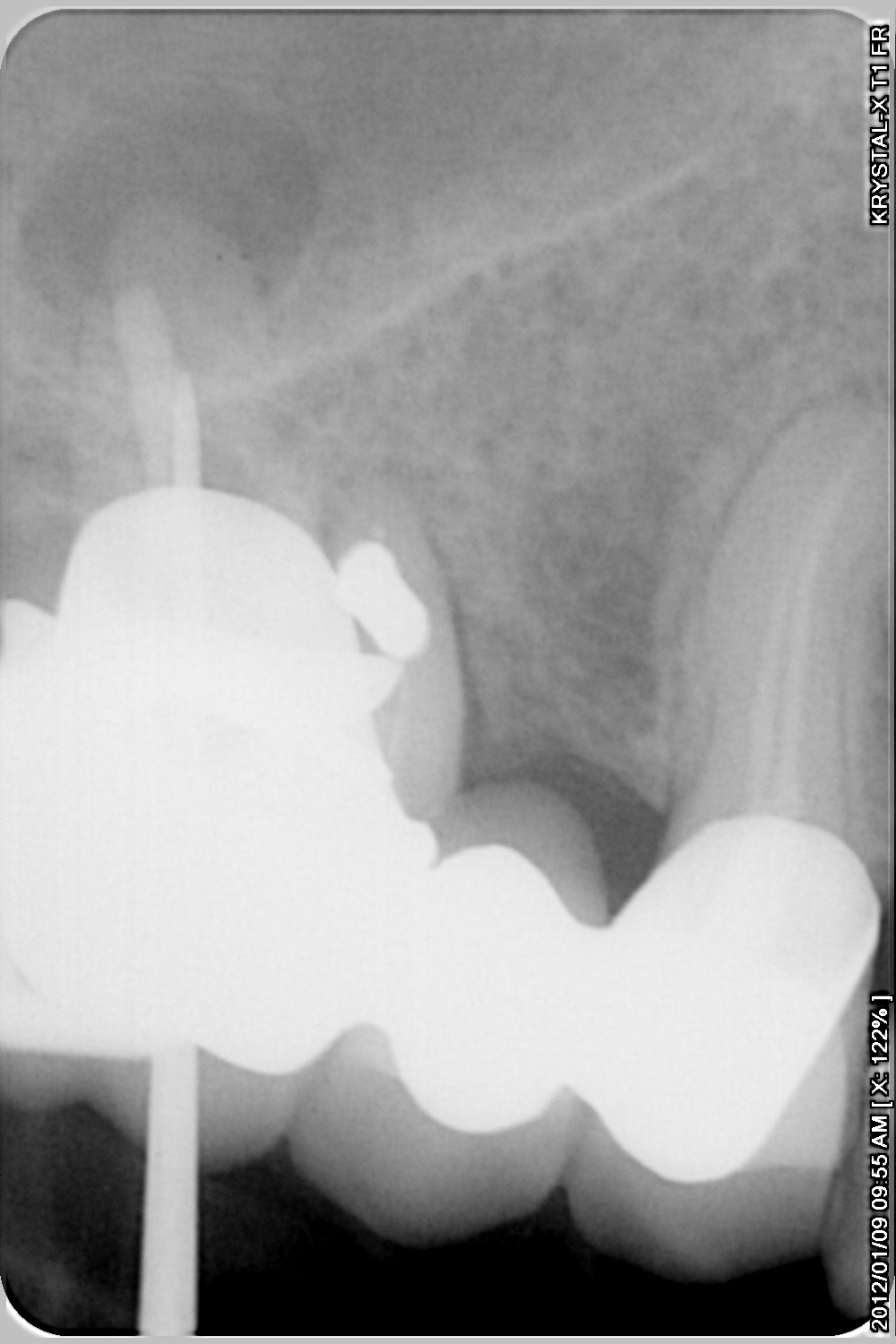

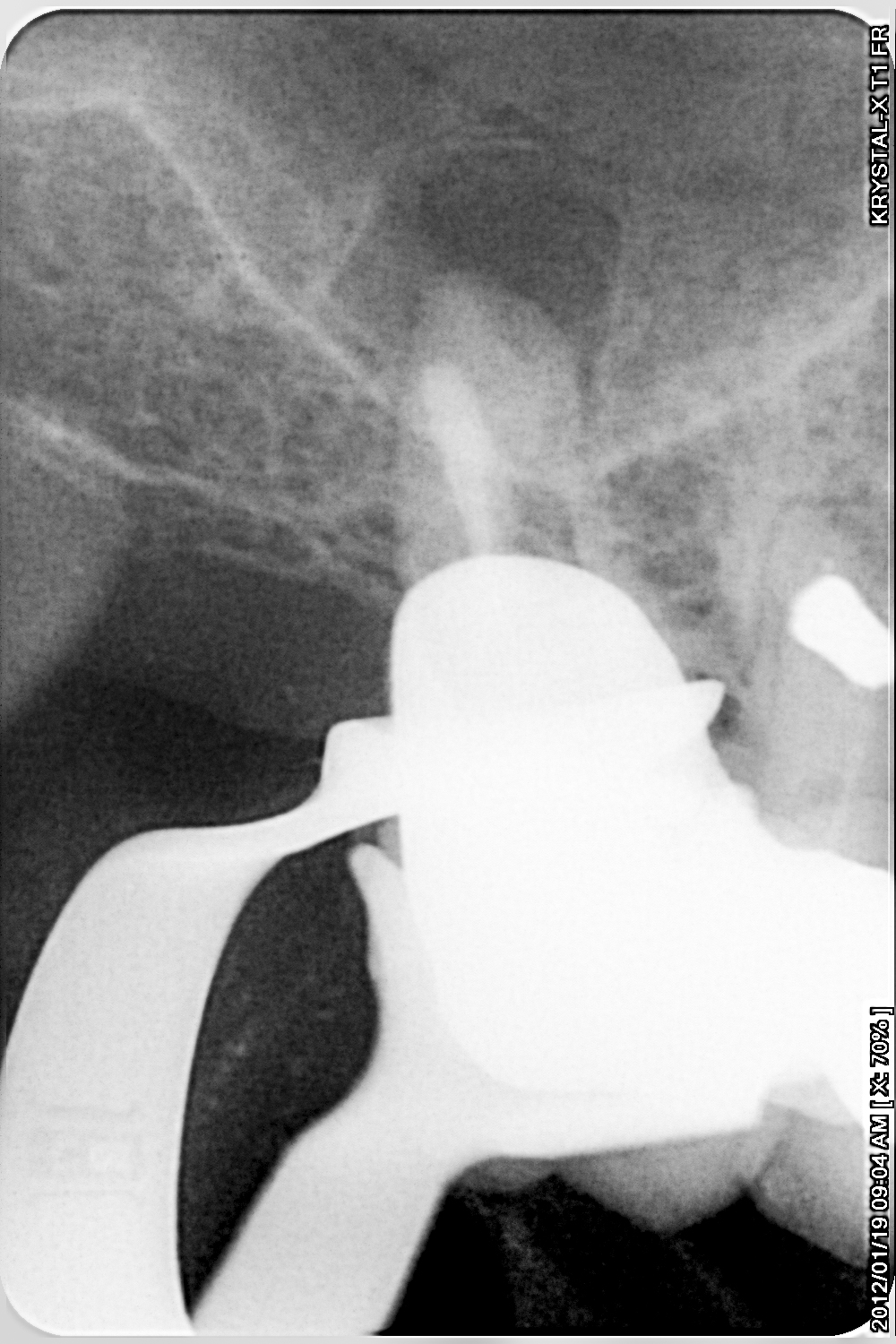

Radiographic examination showed incomplete and ineffective root canal treatment of the molar tooth, the presence of (presumably) amalgam apically of the mesiobuccal root, indicating previous attempts at retrograde filling during apicectomy surgery, and the presence of a large peri-apical radiolucency associated with the palatal root apex. (Figure 2)

A diagnosis of chronic peri-radicular periodontitis of endodontic origin was self-evident. The European dentist referred the patient to the South African endodontic practice with the request to treat the case as conservatively as possible.

The patient relocated to Mozambique and after a period of time consulted me about her condition. She was already aware of the condition of the tooth and the relative absence of bone in the right maxilla, arguably contra-indicating implant placement. She decided and insisted that she wanted to retain the molar tooth at all costs.

I retreated the root canal of the molar tooth as best as possible. (Figures 3 and 4)

The existing bridge was still functioning well and the patient was dismissed in order to await healing. After a period of another year I, in consultation with the patient, decided to surgically remove the distobuccal root in what may be termed a hemisection or root resection procedure. (Figure 5)

At a follow-up consultation three months later healing was confirmed. (Figure 6)

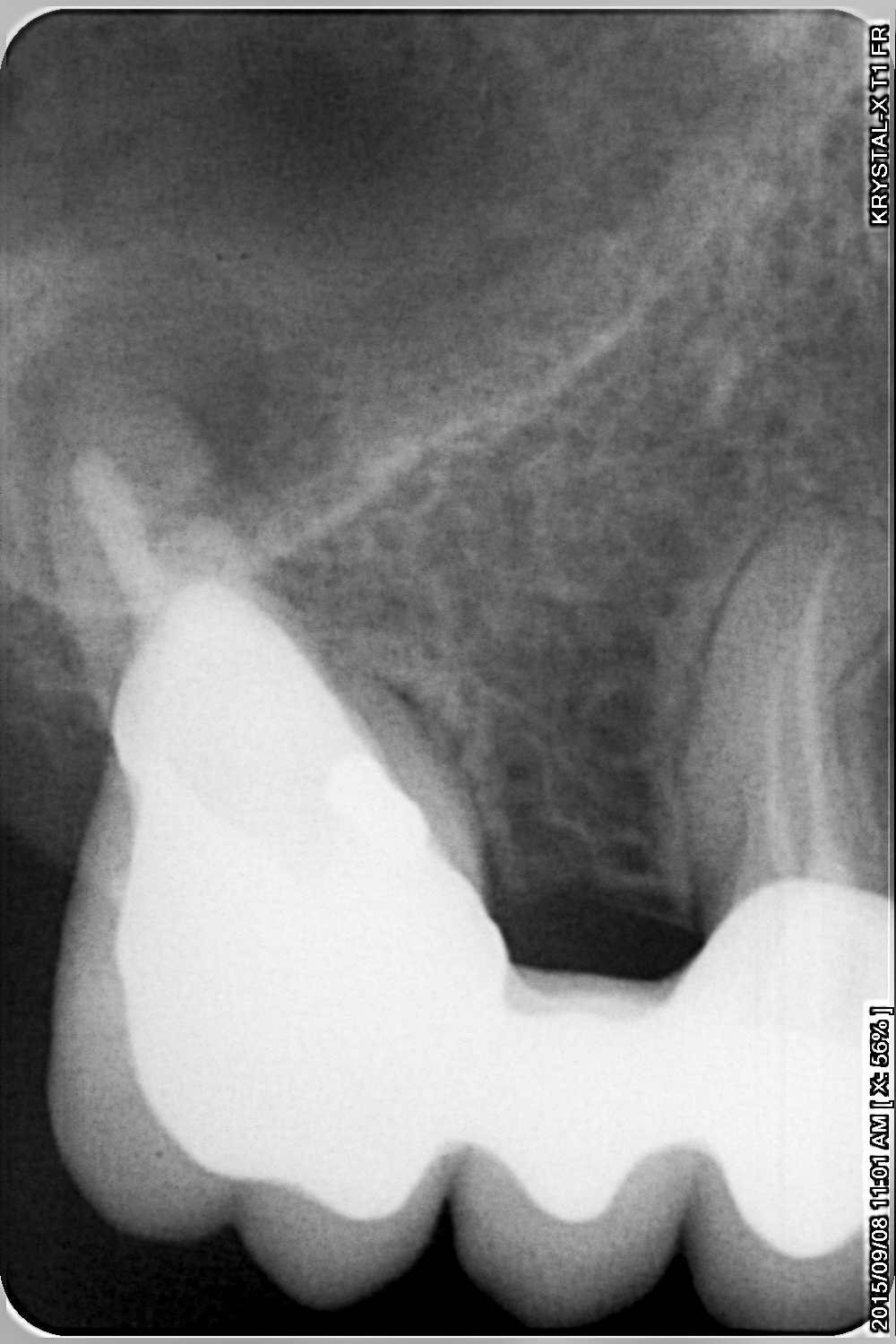

We then decided to replace the old bridge. The old bridge was removed. A radiograph exposed at this time showed the “precarious” situation of this weakened tooth. (Figure 7)

The molar was built up with a core and a new bridge was constructed (Figures 8, 9 and 10) and cemented into position. (Figure 11)

At a one-year recall (Figure 12) and again at twenty months post-operatively (Figure 13) the bridge was found to be sealing and functioning well in all respects. Now, only, was some healing of the peri-apical radiolucency associated with the molar’s palatal root becoming visible. (Figure 14)

Continous, life-long monitoring, is necessary, as with all patients.

This case was shown as an example of “Extreme Endodontics”, a coy reference to the practice of “Extreme Makeovers”, to illustrate how even seemingly hopeless teeth can be successfully treated and maintained to serve as abutments and or restorations.

Obviously, in this day and age, the question that lurks, is that of implant therapy. Why was this not done, in this case? The answer is threefold. Firstly, it is a fact that this case shows an extremely limited amount of bone for implant placement. Secondly, I submit that the counter-argument of bone augmentation is still lacking in scientific foundation, referring to the absence of double blinded, long term, controlled, longitudinal, clinical studies. Thirdly, the patient’s wishes and decision reigned supreme, as always.

I conclude that the profession should heed the advice and warnings implied in this case by not removing teeth before considering all options, including that of “Extreme Endodontics”. |

| Back | Back to top |